Katherine Mansfield’s early stories first published in the

magazine Rhythm, are heavily

influenced by the works of philosopher Henri Bergson. His work introduced two

ways of knowing time: intellectual and intuitive. The former being the way we

formally recognise the time, measured by a series of artificial units and the

latter is the way we “psychologically experience time, or what Bergson calls

‘duration’”. However, the most important aspect of Bergson’s theory is the fact

that spatialised, intellectual time has already passed; it is documented and measured

and can only be represented. A useful allegory for this would be a third person

account of an event that happened. However, intuitive time is a psychological

time, passing right now.

These aspects of the human consciousness are inseparable.

They are created by the degree of tension or relaxation within the

consciousness. When the mind is most tense, the intellect takes over but when

more relaxed, intuition does. This means that our consciousness introduces

different rhythms; it is changeable in terms of its relation to intellect and

intuition.

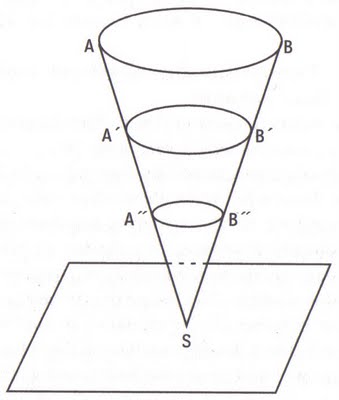

In this sense, it is

integral to consider that Mansfield does not simply write stream of

consciousness narratives because time cannot simply be measured by the

intellect or intuition. This is perfectly illustrated by Bergson, below where

the inverted cone stands on its apex (S) on a rectangular plane (P) with its

base (AB) uppermost:

The cone represents the

totality of the recollections

accumulated in my memory, the base AB, situated in the past, remains

motionless, while the summit S, which represents at all times my present, moves

forward unceasingly also touches the moving plane P of my actual representation

of the universe. At S the image of the body is concentrated; and, since it

belongs to the plane P, this image does not but receive and restore actions

emanating from all images of which the plane is composed.

The present never exists in the intuitive sense, it acts

whereas the past merely exists and does not act, anymore. The past and the

present are “united in the sense that human consciousness moves freely between

them, or anywhere inside the cone”.

Mansfield’s 1910 short story ‘How Pearl Button was Kidnapped’

closely adheres to Bergson’s theories because Pearl’s experiences are

constructed through the co-existence of contradictory intuition and intellect. Indeed,

the title introduces the possibility of violence and shock; however, as the

story progresses, it is clear the reader must identify how Mansfield reveals

this not in the uncanny representation of the Maori community, but in the more

familiar faces, the “little blue men” (or policemen) who ‘kidnap’ Pearl, snatch

her from a place where she enjoys herself and “carry her back to the ‘House of

Boxes’”. Mansfield’s abrupt, matter of fact tone suggests that these men are

the intruders in the narrative. Besides, Pearl never seems to fear her

‘kidnappers’. Mansfield evokes a quasi-maternal bond between them because the

woman “was softer than a bed and she had a nice smell- a smell that made you

bury your head and breathe and breathe it”. Her ‘kidnappers’ are a source of

comfort but it is her family and the police who brutally snatch her from this

happiness and force her to return to her boring life in the “House of Boxes”,

where she is no longer free or mobile.

Mansfield’s style is extremely ambiguous. There are only

three paragraphs in this short story and the reader would expect the first to

break with a temporal conjunction like ‘then’ between the sentences: “She swung

on the little gate, all alone, and she sang a small song” and “Two big women

came walking down the street”. Contrary to the expectations of an adult reader,

events in the story- from Pearl swinging on the gate, the winds blowing up the

street dust, Pearl singing, and the two big women walking towards her- happen

in a continuous flow. This narrative technique implies that within Pearl’s

consciousness, there are no breaks or paragraphs that sort things out

‘intellectually’. The story is told through Pearl’s intuitive consciousness,

where time is experienced as duration rather than as measured and spatialised;

therefore, Mansfield’s narrative could not follow a linear structure.

Mansfield’s methods regarding paragraphing demonstrate how

the narrative is based on the child’s experience of duration. In fact, Pearl

does not does not experience ‘kidnapping’, nor does she identify the two women

as Maori. The reader is invited to follow Pearl’s sense of intuitive perception

instead of intellectual identifications.

However, as Eiko Nakano identifies, Pearl might not know

that the two women can be ethnically described as Maori, but this does not mean

that she does not identify them intellectually. She gives her own definitions

to what she sees or knows both at home and in a new environment. When she is

asked where her mother is, she answers: “In the kitching,

ironing-because-it’s-Tuesday”. The fact that Pearl can immediately link ironing

and Tuesday indicates that she can identify what she knows in an adult,

intellectual way. Similarly, when she goes to sit on the dusty ground: “she

carefully pulled up her pinafore and dress and sat on her petticoat as she had

been taught to sit in dusty places”. As a result of her upbringing, as Nakano

argues, Pearl “instantly reacts to dust and automatically sits in the best way

of sitting in such a place”. As she eats the peach, she worries the juices will

spill onto her clothes. Unlike her mother, Pearl is not trapped within the

‘House of Boxes’, repeating the same ironing every Tuesday, she is mobile. Her

consciousness moves, continually between the intellectual and the intuitive.

The title reinforces the intellectual perspective because we

can take a step into Pearl’s consciousness (where intuition reigns) in a

dreamlike state but it is only when we finish the story (much like waking up)

that we can interpret the story more intellectually and realise that Pearl’s

mother had obviously sent out a search party for Pearl, yet our intuition tells

us that the little blue men, the uncanny yet recognisable figures of policemen

are to take her home to safety. What represent the ‘House of Boxes’ to Pearl,

in fact restores order.

Henri Bergson describes time which is flowing and a time

which has flown with an artistic metaphor: “The finished portrait is explained

by the features of the model, by the nature of the artist, by the colours

spread out onto the palette” but Bergson goes on to explain that not even the

artist could have foreseen how the portrait would turn out “for to predict it

would have been to produce it before it was produced- an absurd hypothesis”. Interestingly,

Mansfield’s title allows the reader to anticipate something before reading it

yet the story turns out differently than expected: the reader is the artist who

creates lives by “reading the story about

these lives”. The reader produces a portrait of the narrative in their

consciousness, open for new interpretations.

Mansfield’s story paints the portrait of Pearl’s

consciousness. Colours are extremely significant because Pearl may

not know what specific things are called, but she takes in the visual richness

of her surroundings. For instance. When she first meets the two women, they are

introduced in relation to the clothes they wear: “One was dressed in red and

the other was dressed in yellow and green. They had pink handkerchiefs over

their heads”. Yet Mansfield’s language is especially perceptive in that Pearl

makes “a cup of her hands” and catches some water from the sea: “it stopped

being blue in her hands”. These changing colours hold a strong resonance because

it describes the way Pearl is a part of nature yet takes part in creating it,

too. She paints the portrait of the external world within her consciousness.

Her excitement at changing the water’s colour, the way “she rushed over to her

woman and flung her little thin arms round the woman’s neck, hugging her, kissing”

is urgent and active but describes the way Pearl creates the scene surrounding

her, inviting the reader into her consciousness to experience that same excitement.

The significance of intellectual and intuitive time in Bergson’s

theory is indivisible in his philosophy and in Mansfield’s writing. Location is

a significant feature in her early works but what makes Mansfield stand out as

a Modernist writer is her ability to express the ways in which her characters

experience time as linear and spatialised as well as intuitive.

Niamh Hughes

Works Cited

Bergson, Henri, Creative Evolution, A. Mitchell (trans.)

(London: Macmillan, 1911)

-Matter and Memory, N.M. Paul and

W.S. Palmer (trans.) (London: Allen and Unwin, 1911)

Mansfield, Katherine, ‘How Pearl Button Was Kidnapped’ in

Selected Stories (Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 2002)

Nakano, Eiko, ‘Katherine Mansfield, Rhythm and Henri

Bergson’ in Katherine Mansfield and Literary Modernism eds. Gerri Kimber, Susan

Reid & Janet Wilson (London: Continuum, 2011)

Nice post.

ReplyDelete